Ground Water

Oil spills

Another chronic problem in many rural homes is leaking or spilled fuel oil

which eventually contaminates the owner's own well. Many homes have a fuel tank,

either buried or above ground, adjacent to the house and within a few feet of

the well. Spills or accumulated leakage eventually can migrate to the aquifer

and can be drawn into the well, making it unusable for years. Usually the only

solution is to obtain a new water source. In some instances, however, reducing

the pumping rate to reduce drawdown allows the oil to float on the water surface

safely above the well's intake area.

Methane gas

Perhaps the problem that poses the greatest hazard to a well owner is

flammable gas in the well. Small volumes of natural gas, usually methane, can be

carried along with the water into wells tapping carbonate or shale rock. In some

areas, the gas dissipates soon after installation of the well, but, in other

areas, a large continual source of natural gas remains. Because methane is

flammable and cannot be detected by smell, precautions are needed to prevent

explosions and fire. Venting of the well head to the open air is the simplest

precaution but, because gas can also accumulate in pump enclosures, pressure

tanks, and basements, other venting may be needed. For this reason, a home

should never be built over a well.

Bacteria

The most common water-quality problem in rural water supplies is bacterial

contamination from septic-tank effluent. A recent nationwide survey by the U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency and Cornell University found that contamination

of drinking water by septic effluent may be one of the foremost water-quality

problems in the Nation.

|

| How septic effluent percolates to the water table. |

Barnyard runoff

Probably the second most serious water-contamination problem in rural farm

homes is from barnyard waste. If the barnyard is upslope from the well, barnyard

waste that infiltrates to the aquifer may reach the well. Pumping, too, can

cause migration of contaminants to the well. On many farmsteads built more than

100 years ago, the builders were careful to place the supply well upslope from

the barnyard. Unfortunately, many present-day owners have not remembered this

basic principle and have constructed a new house and well downslope of the

barnyard.

|

| Barnyard upslope from farmhouse well may cause bacterial

contamination of water supply. (Photograph courtesy Cornell

University.) |

Pesticides and fertilizers

The last 3 decades have seen a significant increase in small part-time farms

and rural dwellings as large farms have been sold and divided into smaller

units. Many modern rural homes are constructed on former cropland on which heavy

applications of herbicides and fertilizers may have been made. How these

chemicals move through the soil and ground water and how quickly they decompose

or how their harmful effects are neutralized is not well understood.

|

| New home on land recently used for crops. |

Also common is the farming practice of applying fertilizers and pesticides to

croplands immediately adjacent to the barnyard or farmyard. Residue from these

applications can infiltrate to the aquifer and can be drawn into a supply well

for the barn or the house. Decreasing the use of fertilizers and pesticides in

the vicinity of wells can help minimize this problem.

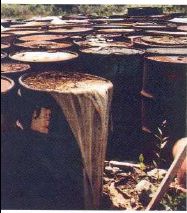

Homeowners also should be careful to properly dispose of wastewater from used

containers of toxic chemicals. Many farms have their own disposal sites,

commonly pits or a wooded area, for garbage and the boxes, sacks, bottles, cans,

and drums that contained chemicals. Unfortunately, these owner disposal sites

can contaminate farm water supplies.

|

| Pesticide spraying near well. |

Septic Systems and Ground Water

The liquid effluent from a septic system follows the same path as the rain or

snowmelt that percolates into the unsaturated zone. Like the rain, once the

effluent reaches the water table, it flows down the hydraulic gradient, which

may be roughly parallel to the slope of the land, to lower points. Thus, again,

the location of one's house in relation to neighboring houses, both upslope and

downslope, is important.

Septic-tank effluent that enters the aquifer supplying the homeowner's well

introduces not only bacteria but also other contaminants. Many rural homeowners

also discharge other waste products, including toxic material, into their septic

systems, and these products gradually accumulate in the aquifer. What happens to

these contaminants in the ground is not well known. Some adhere to rock

material, others travel with the water. In some types of rock material, the

leach field or dry-well part of the septic system can gradually become clogged

by contaminants.

Rural homes in small, older communities and in more recent roadside housing

developments are commonly situated on small or narrow lots along an access

highway. Most do not have a community water supply, and almost all have their

own individual septic systems. In clusters such as this, effluent recycling can

occur if the wells are shallow or the septic systems are improperly placed. Deep

wells are less likely to draw in septic waste.

|

| Rural roadside housing development. |

This type of effluent problem becomes acute in an area underlain by a shallow

water-table aquifer where the septic effluent discharges into water that is used

by many homeowners. This dilemma has been posed in many rural housing

developments throughout the Nation. One either "fouls his own nest" with

effluent or connects to a central sewer system. Although a sewer system protects

the aquifer from further contamination, it reduces recharge of water to the

aquifer. This engineering, economic, and social dilemma must be resolved soon in

many areas. An increasing number of counties and townships are planning and

zoning rural areas to limit the density of houses according to soil conditions.

Other approaches being considered are a community water supply with individual

septic systems or individual water supplies with a community sewer system.

Some banks and lenders require that the prospective buyer or the seller

furnish proof of a bacteria-free water supply before they will issue a mortgage.

When a seller faces such a requirement, a common procedure is to chlorinate the

water to destroy the bacteria in the well. This treatment affects only the well

and perhaps a volume of the aquifer immediately adjacent to the well, but for

only a brief time. If the contamination is in the aquifer, the source will not

be attacked nor the problem solved ; thus a water analysis showing bacteria-free

water immediately after the well has been disinfected is not necessarily an

assurance of a safe water supply. The homeowner should periodically have the

water analyzed for bacteria. If a high bacteria count occurs repeatedly, the

problem is probably in the water source, and chemical treatment of the well

alone cannot solve it.

In a bacteria-contaminated water system, chlorination of the water pumped

from the well is commonly recommended as a solution. Other-wise, one must obtain

a water supply from a new well that either is upgradient from the contaminating

source or that taps a deeper aquifer. Moving the septic system to a more distant

spot is a long-term solution, but the underlying contaminated zone may take

years to stop releasing contaminants to the aquifer.

Cluster-housing contamination

In a row-housing setting, the house at the highest location will generally

have the safer water supply. Because the effluent migrates down beneath the

development, it could be pumped, used, and again discharged by each house along

its course. The house furthest downslope would receive the combined effluent

from the other houses.

Another contamination problem from closely spaced septic systems can occur

where a row of houses on the uphill side of a road faces a row of houses on the

downhill side of the road. Here, the safer water supply would be on the uphill

side. The downhill side would receive effluent from the uphill side plus any

contamination generated along the road, such as road salt or metal compounds. In

flat areas underlain by a shallow water table, especially where cluster

developments are two or more decades old, almost perpetual recycling of septic

waste may occur.

Another source of contamination that is common in villages or hamlets lacking

a central water or sewage system is small waste-generating businesses such as

laundries, auto-repair shops, and industries that discharge wastes to their own

septic systems. Many of the bacterial problems, cited in a recent U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency rural water study, were in hamlets, villages, or

crossroads communities. Once indoor plumbing became common and outdoor privies

were removed, all waste went into septic systems from which increased amounts of

liquid effluent eventually entered the aquifer and became subject to pumping by

wells.

Unknown Hazards Beneath the Land

Previous land uses, some of which may be unknown to the present landowner,

can have long-lasting effects on the land and on underlying aquifers.

|

| Hidden dump site may contain chemical-waste containers. |

Former chemical dump sites

Many sites where commercial and industrial wastes are buried have been

abandoned and have been covered with soil or have become revegetated. In many

such areas, individual homes or entire housing developments have been built

without proper consideration of the buried waste. (The tragedy of Love Canal,

near Niagara Falls, N.Y., is an unfortunate example of construction over

concealed waste.) A prospective land buyer, home builder, or buyer of a recently

built rural home should inquire of local agencies about the former use of the

land.

Abandoned wells

Although still relatively rare, waste sites can be abandoned wells that are

now used for disposal of wastes, commonly oil or laundry wastes. Many garages

and repair shops have used abandoned drilled wells for disposal of waste oil,

and laun-dries have used abandoned dug wells for disposal of laundry wastes to

prevent clogging of their septic systems. These practices point to an area where

concern for ground-water protection should be considered more carefully.

Abandoned wells should be filled and sealed properly to eliminate the danger of

someone falling into the well or having the shaft collapse, as well as to remove

the temptation to use them for disposal of hazardous wastes.

|