Local anesthetic agents and their history

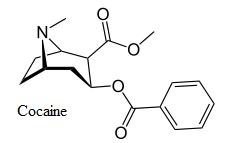

Surprisingly, the first local anesthetic was Cocaine which was

isolated from coca leaves by Albert Niemann in Germany in the 1860s. The very

first clinical use of Cocaine was in 1884 by (of all people) Sigmund Freud who

used it to wean a patient from morphine addiction. It was Freud and his

colleague Karl Kollar who first

noticed

its anesthetic effect. Kollar first introduced it to clinical ophthalmology as

a topical ocular (eye) anesthetic. Also in 1884, Dr. William Stewart Halsted

was the first to describe the injection of cocaine into a sensory nerve trunk to

create surgical anesthesia. Halsted was an eminent surgeon who had been trained

in Britain. He was the first to establish formal surgical training for

physicians in America. Prior to that time, surgery was a self taught discipline

among US physicians. He also invented and pioneered the use of rubber gloves.

Unfortunately, much to his own regret, he began to use cocaine himself and

became highly addicted to it. At that time, there was no stigma attached to the

recreational use of cocaine, and it gained a following among the elites of the

day. Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes was supposed to be an addict, and

Holmes kept Dr Watson around as a source for his drugs, as well as for the comic

relief he provided.

noticed

its anesthetic effect. Kollar first introduced it to clinical ophthalmology as

a topical ocular (eye) anesthetic. Also in 1884, Dr. William Stewart Halsted

was the first to describe the injection of cocaine into a sensory nerve trunk to

create surgical anesthesia. Halsted was an eminent surgeon who had been trained

in Britain. He was the first to establish formal surgical training for

physicians in America. Prior to that time, surgery was a self taught discipline

among US physicians. He also invented and pioneered the use of rubber gloves.

Unfortunately, much to his own regret, he began to use cocaine himself and

became highly addicted to it. At that time, there was no stigma attached to the

recreational use of cocaine, and it gained a following among the elites of the

day. Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes was supposed to be an addict, and

Holmes kept Dr Watson around as a source for his drugs, as well as for the comic

relief he provided.

It became fairly obvious fairly quickly that while the

anesthetic characteristics of cocaine were desirable, the euphoria and

subsequent addiction it produced were not! The turn of the century was a

tremendous time of scientific progress, and the new discipline of

organic

chemistry enabled the synthesis of the first analog of cocaine in 1905. (An

analog of a chemical molecule is one in which the original molecule is

progressively modified to retain and enhance certain holistic characteristics of

the original substance while ridding it of other unwanted characteristics.) The

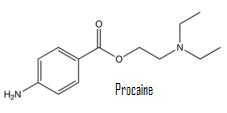

first synthetic local anesthetic was procaine, better remembered today by

its trade name, "Novocain".

organic

chemistry enabled the synthesis of the first analog of cocaine in 1905. (An

analog of a chemical molecule is one in which the original molecule is

progressively modified to retain and enhance certain holistic characteristics of

the original substance while ridding it of other unwanted characteristics.) The

first synthetic local anesthetic was procaine, better remembered today by

its trade name, "Novocain".

Novocain was not without its problems. It took a very long time

to set (ie. to produce the desired anesthetic result), wore off too quickly and

was not nearly as potent as cocaine. On top of that, it is classified as an

ester. Esters have a very high potential to cause allergic reactions. It is

estimated that about one third of all persons who received it developed at least

minor allergic reactions to it. Faced with the legal and ethical difficulties

associated with the use of cocaine as a local anesthetic, and with the

inefficiencies and allergenicity associated with the use of procaine, it is not

surprising that most dentists of the day worked without any local anesthetic at

all. (Nitrous oxide gas was available during this period.) Today, procaine is

not even available for dental procedures.

| In 1942, W.C. Fields made a movie called "The dentist". It was

a bawdy, slapstick comedy short (25 minutes) which included scenes

of Fields as a dentist working on patients, complete with the sound

of a buzz saw. It was, of course, meant to be funny, but it shows a

patient squirming in the dental chair, and in this sense, at least,

was probably not far from the truth about dentistry up until shortly

after the film was made. You can download a clip from the film

here. (The link to the clip is near

the bottom of the page) |

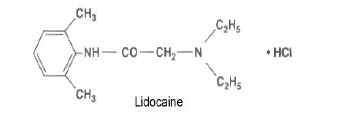

The

first modern local anesthetic agent was lidocaine (trade name

Xylocaine�). It was invented in the 1940s. Prior to its introduction,

Nitrous oxide gas and procaine (plus alcohol in the form of whiskey) were the

major sources of pain relief during dental procedures. Lidocaine proved to be

so successful that during the 1940s and 1950s the use of procaine and nitrous

oxide gas as primary anesthetic agents all but vanished. (Whiskey somehow

survived, but it is no longer used on patients.) Today, nitrous oxide is

used principally as an anti-anxiety palliative, and Novocaine is no longer

available.

The

first modern local anesthetic agent was lidocaine (trade name

Xylocaine�). It was invented in the 1940s. Prior to its introduction,

Nitrous oxide gas and procaine (plus alcohol in the form of whiskey) were the

major sources of pain relief during dental procedures. Lidocaine proved to be

so successful that during the 1940s and 1950s the use of procaine and nitrous

oxide gas as primary anesthetic agents all but vanished. (Whiskey somehow

survived, but it is no longer used on patients.) Today, nitrous oxide is

used principally as an anti-anxiety palliative, and Novocaine is no longer

available.

Lidocaine (along with all other injectable anesthetics

used in modern dentistry) is in a broad class of chemicals called amides, and

unlike ester based anesthetics, amides are hypoallergenic. It sets

quickly and when combined with a small amount of

epinephrine (adrenalin), it produces

profound anesthesia for several hours. Lidocaine is still the most widely used

local anesthetic in America today.

Over the next thirty years, a number of other amide local

anesthetics were invented, most not differing significantly from lidocaine. The

major problem with lidocaine and its analogs is that they cause vasodilation,

or the tendency of the local blood vessels to open wider increasing the blood

flow in the area. This causes the anesthetic to be absorbed too quickly to take

effect. Hence these anesthetics are always mixed with low concentrations of

epinephrine which has the opposite effect (ie vasoconstriction) and

closes the blood vessels down to keep the anesthesia in position long enough to

produce long lasting numbness.

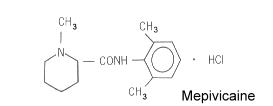

Mepivicaine

(Carbocaine�) and prilocaine (Citanest�)

have much less vasodilative qualities and hence can be used without the

epinephrine vasoconstrictor. The advantage to this is that these anesthetics

can be used more safely in patients who are taking medications which may

interact negatively with the vasoconstrictor. These drugs include certain blood

pressure medications (most notably non selective beta blockers) and tricyclic

antidepressants (Elevil� and imipramine are two examples). Carpules that do

not contain the vasoconstrictor also do not contain a preservative. This

eliminates a possible source of allergic reaction.

Mepivicaine

(Carbocaine�) and prilocaine (Citanest�)

have much less vasodilative qualities and hence can be used without the

epinephrine vasoconstrictor. The advantage to this is that these anesthetics

can be used more safely in patients who are taking medications which may

interact negatively with the vasoconstrictor. These drugs include certain blood

pressure medications (most notably non selective beta blockers) and tricyclic

antidepressants (Elevil� and imipramine are two examples). Carpules that do

not contain the vasoconstrictor also do not contain a preservative. This

eliminates a possible source of allergic reaction.

Bupivicaine (Marcaine�)

Bupivicaine is a special case in dental anesthesia. It is used

mostly by surgeons who want to produce very long acting anesthetic effects in

order to delay the post operative pain from their surgery for as long as

possible. Bupivicaine comes in 0.5% solution with a vasoconstrictor. It is the

most toxic of all the anesthetic agents and this toxicity is reflected in its

low concentration in the carpules. As noted in the

PKa table, it is has a very alkaline (basic)

PKa which means that a relatively low percentage of the uncharged base radical

(RN) is available for immediate diffusion through the

cell membrane. Thus it takes a fairly long

time to set. However, once inside the cell membrane, over 80% of the radicals

that do diffuse become available for binding to the sodium channel proteins.

This high protein binding ability causes the drug to remain active for a long

time once it has diffused through the cell membrane. (PKa and its relationship

with cell membrane permeability is a concept explained

later in this course.)

Prilocaine

(Citanest�)

Prilocaine

(Citanest�)

Prilocaine has the same general

PKa as lidocaine, which means that for all

practical purposes it can be used in the same way and at the same concentrations

as lidocaine, producing about the same anesthetic affect in the same setting

time for the same duration. It is, however somewhat

less toxic in higher doses than lidocaine, and

thus is delivered in a 4% solution which places about twice as much molecular

anesthetic in proximity to the nerve as is the case with lidocaine or

mepivicaine. In addition, since it has little vasodilatory activity, it may be

used without a

vasoconstrictor. The higher concentration of

anesthetic agent, in combination with a vasoconstrictor, therefore, gives this

anesthetic the twin advantages of fast onset of activity with prolonged

anesthetic activity due to the larger number of molecules available to cross the

cell membrane. Unfortunately, the toxicity of a single carpule of 4% prilocaine

is still greater than the toxicity of a single carpule of 2% lidocaine which

means that fewer carpules can be used before toxic levels are reached. Higher

toxicity translates into a higher likelihood of prolonged or permanent

paresthesia or anesthesia after using this drug for major nerve blocks.

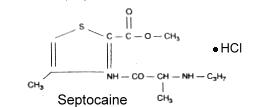

Articaine (Septocaine�)

Articaine is the newest addition to the local anesthetic arsenal

and was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in April 2000. It has been

in use in Europe since 1976 and in Canada since 1983. Its approval in the US

has been delayed by the FDA due to the presence of a preservative which the

agency said was unnecessary in single use carpules and was a potential allergen.

It was approved when the French company Septodent finally removed the

preservative from American shipments.

Articaine

has the same

PKa and toxicity as Lidocaine, however it is

metabolized differently. It has a half life in the body less than 1/4 as long

as that of lidocaine and only 1/5 as long as mepivicaine. This means that more

of the drug can be injected later in the dental procedure with less likelihood

of blood concentrations building to toxic levels. Articaine is formulated in a

4.0% solution with

vasoconstrictor. The presence of the

vasoconstrictor retards the systemic absorption of the anesthetic allowing

higher concentrations of the drug to remain in the area of injection and slowing

the absorption into the bloodstream. The higher local concentration of the drug

produces a high level of the uncharged radical (RN) to be present at the

membrane which brings about very rapid absorption of the drug. (The concept of

membrane permeability is discussed on

page 4 in this course.) In addition, the

benzene ring on the left end of the molecule has been replaced with a thiophene

ring. This modification allows for faster and more complete absorption through

the nerve cell membrane. The ability of this drug to penetrate barriers is so

great that it has been used to penetrate thick bone to produce anesthesia in a

way that other anesthetics cannot. Articaine has become the local anesthetic of

choice in most countries into which it has been introduced. I have found that

it produces profound anesthesia (in most patients) when used as an infiltration

(field block) for mandibular premolars and anterior teeth instead of the

traditional mandibular nerve block..

Articaine

has the same

PKa and toxicity as Lidocaine, however it is

metabolized differently. It has a half life in the body less than 1/4 as long

as that of lidocaine and only 1/5 as long as mepivicaine. This means that more

of the drug can be injected later in the dental procedure with less likelihood

of blood concentrations building to toxic levels. Articaine is formulated in a

4.0% solution with

vasoconstrictor. The presence of the

vasoconstrictor retards the systemic absorption of the anesthetic allowing

higher concentrations of the drug to remain in the area of injection and slowing

the absorption into the bloodstream. The higher local concentration of the drug

produces a high level of the uncharged radical (RN) to be present at the

membrane which brings about very rapid absorption of the drug. (The concept of

membrane permeability is discussed on

page 4 in this course.) In addition, the

benzene ring on the left end of the molecule has been replaced with a thiophene

ring. This modification allows for faster and more complete absorption through

the nerve cell membrane. The ability of this drug to penetrate barriers is so

great that it has been used to penetrate thick bone to produce anesthesia in a

way that other anesthetics cannot. Articaine has become the local anesthetic of

choice in most countries into which it has been introduced. I have found that

it produces profound anesthesia (in most patients) when used as an infiltration

(field block) for mandibular premolars and anterior teeth instead of the

traditional mandibular nerve block..

With clinical reports of profound anesthesia, fast onset, and

success in difficult-to-anesthetize patients, Septocaine has become the most

used dental anesthetic brand name in the US, although lidocaine still remains

the most used type of anesthetic. Recently, the same articaine formulation

became available from a second company under the name Cook-Waite Zorcaine.

Because of its bone penetrating ability, articaine has become

popular for producing profound anesthesia in lower premolars and lower anterior

teeth using localized field blocks (infiltrations) without resorting to

mandibular blocks.

Articaine and prolonged numbness and

paresthesia

Unfortunately, one complication concerning the use of

articaine has arisen. There have been persistent reports of unexplained

paresthesia (burning, tingling, ans sometimes sharp shooting pains in

tissues previously anesthetized with this anesthetic) in a low

percentage of patients. This effect has been noted only when articaine is

used in

major nerve blocks such as the mandibular

block. It has not been noted in

field blocks. So far, no common factor has

been found to explain the link between articaine and persistent paresthesia,

however the higher concentration of anesthetic molecules in the anesthetic

solution (4% for articaine instead of 2% for lidocaine or 3% for mepivicaine

without vasoconstrictor) probably is a factor. The statistics produced for

this phenomenon so far have been quite inconsistent. The incidence for

persistent paresthesia have ranged between 1 in 5,286 for 2002 to 1 in

45,900 in 2004. The incidence for persistent paresthesia for other types of

dental local anesthetic solutions ranged between 1 in 25,850 to 1 in 68,675

during the same timeframe (all statistics approximate; CRA June 2005; vol

29, issue 6).

-

10% of cases of paresthesia lasted for 24 hours or less.

-

52% of cases of paresthesia lasted 1 to 4 weeks.

-

29% of cases of paresthesia lasted 1 month to 1 year.

-

10% of cases of paresthesia lasted for over a year.

-

The most common link with articaine and paresthesia was

administration of mandibular nerve block injections. For this

reason a number of dentists have abandoned the use of articaine for

mandibular nerve blocks, but still use it for infilatration anesthesia

(field blocks) of mandibular anterior teeth and bicuspids.

Treatment of anesthesia and paresthesia

I am not aware of any specific way to treat the numbness

caused by Articaine (other than waiting out the effect), however the

disruptive and often painful paresthesia, including the shooting pains in

the distribution of the affected nerves may be controlled with certain anti

convulsant drugs. One such drug is Lyrica (Pregabalin) 50 mg. three

times a day. Two older drugs in this category are Neurontin (gabapentin)

and Tegretol (carbamazepine).